A peek inside Physical Intelligence, the startup building Silicon Valley’s buzziest robot brains

Inside Physical Intelligence, the fast-growing robotics startup is developing general-purpose robot intelligence and drawing major funding as Silicon Valley races to build smarter machines.

From the outside, there’s almost nothing to suggest that one of Silicon Valley’s most talked-about robotics startups operates behind an unassuming door in San Francisco. The only clue is a small pi symbol on the entrance, rendered in a shade just different enough to stand out if you’re paying close attention. Inside, the scene is immediately alive. There’s no front desk, no glowing signage, no polished lobby meant to impress visitors.

Instead, the headquarters of Physical Intelligence opens into a cavernous concrete space softened only by a loose arrangement of long, pale wooden tables. Some serve as casual dining spots, scattered with Girl Scout cookie boxes, jars of Vegemite—an unmistakable nod to an Australian presence—and wire baskets crowded with condiments. Others tell a very different story. Those are covered with computer monitors, spare robotic components, coils of black cable, and robotic arms at various stages of learning how to do ordinary human tasks.

During my visit, one robotic arm is attempting to fold a pair of black pants. The effort is earnest, but unsuccessful. Another is determinedly trying to turn a shirt inside out, persisting with the kind of mechanical focus that suggests it will eventually succeed—just not today. A third arm appears to have found its niche: peeling a zucchini. It performs the task efficiently, producing neat ribbons of vegetable that it is meant to deposit into a separate container. At least that part is working.

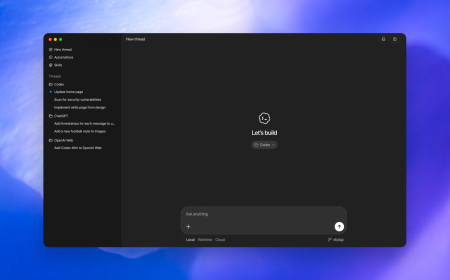

“Think of it like ChatGPT, but for robots,” says Sergey Levine, gesturing toward the synchronized motion unfolding across the room. Levine, an associate professor at UC Berkeley and one of Physical Intelligence’s co-founders, has the calm, approachable demeanour of someone accustomed to breaking down complex ideas for an audience abroad.

What’s happening here, he explains, is part of a continuous feedback loop. Data is collected from robotic stations inside this building and at other locations—warehouses, homes, anywhere the team can place equipment. That data feeds into general-purpose robotic foundation models. When a new model is trained, it returns to stations like these for testing and evaluation. The struggling pants-folder is someone’s experiment. So is the shirt-turner. The zucchini peeler may be assessing whether the model can generalize its peeling technique across different foods, learning motions that apply equally well to an apple or a potato it has never seen before.

The company also runs test kitchens here and at other sites, using readily available hardware to expose robots to varied environments and challenges. A high-end espresso machine sits nearby. At first glance, it looks like an employee perk, until Levine clarifies that it’s there for the robots, not the staff. Any latte art produced is more data for the system, not a reward for the engineers who fill the room, most of whom are focused intently on their screens or hovering near their robotic setups.

The hardware itself is intentionally unimpressive. Each robotic arm costs around $3,500, which Levine notes includes an enormous markup from the supplier. If the company manufactured the arms itself, the materials would cost under $1,000. Not long ago, he says, many roboticists would have been amazed that such inexpensive machines could function at all. That’s precisely the point: strong Intelligence can compensate for hardware limitations.

As Levine steps away, I’m soon joined by Lachy Groom, who moves through the space with the urgency of someone juggling multiple priorities. At 31, Groom still carries the aura of a Silicon Valley prodigy. He earned that reputation early, having sold his first company just nine months after founding it at age 13 in Australia—a background that neatly explains the Vegemite on the tables.

Earlier, when I first asked for time with him as he greeted a small group of hoodie-clad visitors, his response was blunt: “Absolutely not, I’ve got meetings.” Now, he has ten minutes. Maybe.

Groom says he became interested in Physical Intelligence after closely following academic research from the labs of Levine and Chelsea Finn, a former Berkeley PhD student of Levine’s who now leads her own robotics learning lab at Stanford University. Their names kept appearing in nearly every meaningful piece of work in robotics. When Groom heard they might be starting a company, he tracked down Karol Hausman, a researcher at Google DeepMind who also taught at Stanford and was rumoured to be involved. “It was just one of those meetings where you walk out thinking, This is it,” Groom recalls.

Despite his success as an investor, Groom never planned to make that his permanent role. After leaving Stripe, where he was an early employee, he spent roughly five years as an angel investor, backing companies such as Figma, Notion, Ramp, and Lattice while searching for the right opportunity to build or join something himself. His first robotics investment, Standard Bots, came in 2021 and rekindled a childhood fascination sparked by building Lego Mindstorms. As he jokes, investing felt like being “on vacation” compared to it. Still, it was a means to stay engaged, not the destination.

“I was looking for five years for the company to go start post-Stripe,” he says. “Good ideas at a good time with a good team—that’s extremely rare. You can execute flawlessly on a bad idea and still end up with a bad outcome.”

Now two years old, Physical Intelligence has raised more than $1 billion. Groom is quick to point out that despite the headline figure, the company’s burn rate isn’t exceptionally high. Most of its spending goes toward computing. That said, under the right conditions and with the right partners, he wouldn’t rule out raising more. “There’s no real limit to how much money we can put to work,” he says. “You can always use more compute.”

What sets the company apart is not just how much capital it has raised, but what Groom doesn’t promise investors. He doesn’t offer a roadmap for monetization. Backers—which include Khosla Ventures, Sequoia Capital, and Thrive Capital—have valued the company at $5.6 billion despite the absence of a commercialization timeline. “I don’t give investors answers on commercialization,” Groom says. “It’s kind of strange that people accept that.” For now, they do, which is one reason the company has prioritized building a substantial financial cushion.

So what is the strategy, if not immediate revenue? Another co-founder, Quan Vuong, formerly of Google DeepMind, explains that the focus is on cross-embodiment learning and highly diverse data. The goal is to ensure that if a new robotic platform appears tomorrow, it won’t require starting from scratch. Existing knowledge can be transferred directly. “The marginal cost of adding autonomy to a new robot platform is much lower,” Vuong says.

Physical Intelligence is alreadyIntelligenceng with a small number of companies across logistics, grocery, and even a nearby chocolate manufacturer, testing whether its systems are ready for real-world automation. In some cases, Vuong says, they already are. By pursuing an “any platform, any task” philosophy, the company can identify and deploy automation opportunities as soon as they become viable.

The company isn’t alone in chasing this ambition. The race to build general-purpose robotic Intelligence—the equivalent ofthe models for physical machines—is intensifying. Pittsburgh-based Skild AI, founded in 2023, recently raised $1.4 billion at a $14 billion valuation and has taken a notably different approach. While Physical Intelligence remains focused on research, Skild AI has already commercialized its “omni-bodied” Skild Brain, reporting $30 million in revenue within months across sectors such as security, warehousing, and manufacturing.

Skild has also publicly criticized competitors, arguing on its blog that many so-called robotics foundation models are essentially repackaged vision-language systems that lack a truly physical understanding because they rely too heavily on internet-scale pretraining rather than on physics-based simulation and real-world robotics data.

It’s a sharp philosophical divide. Skild AI is betting that commercial deployment creates a powerful data flywheel. Physical Intelligence is betting that near-term commercialization will ultimately yield more capable general Intelligence. Determining Intelligence is right, and it will likely take years.

In the meantime, Groom describes Physical Intelligence as operating with rare clarity. “It’s a very pure company,” he says. “A researcher has a need, we collect the data or build the hardware to support that need, and we move forward. It’s not driven by external pressures.” The team initially mapped out what they believed could be achieved over five to ten years. According to Groom, they surpassed that roadmap within 18 months.

The company employs about 80 people and plans to grow, though Groom hopes the pace remains slow. Hardware, he says, is the hardest part. “Hardware is just really hard. Everything takes longer. Things break. Deliveries are delayed. Safety adds another layer of complexity.”

As the groom hurries off to his next meeting, the robots continue their quiet training. The pants remain imperfectly folded. The shirt is still right-side-out. The zucchini shavings, however, keep piling up neatly.

There are plenty of open questions—whether consumers actually want robots handling food in their kitchens, how safety concerns will be addressed, how pets might react, and whether the immense time and capital invested here will solve meaningful problems or create new ones. Sceptics also question the company’s progress and whether betting on general Intelligence or specific overtargeting Intelligence makes sense.

If the groom harbours doubts, he doesn’t reveal them. He’s surrounded by people who have spent decades working on these challenges and who believe the timing is finally right. For him, that’s enough.

After all, Silicon Valley has long placed big bets on people like Groom, granting them latitude even in the absence of clear commercialization plans or timelines. It doesn’t always work. But when it does, it tends to justify the many times it didn’t.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0