Why the economics of orbital AI are so brutal

Orbital AI promises real-time data processing from space, but high launch costs, satellite hardware limits, and narrow revenue models make its economics challenging.

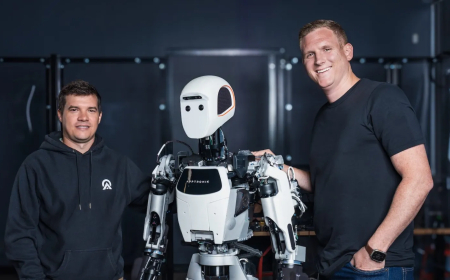

In many ways, the push toward artificial intelligence infrastructure in orbit feels unavoidable. Elon Musk and those around him have long discussed the concept of AI operating in space, often referencing Iain Banks' far-future novels depicting intelligent spacecraft governing interstellar civilisations.

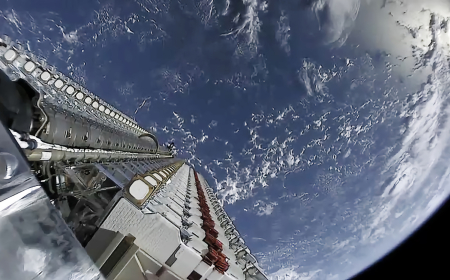

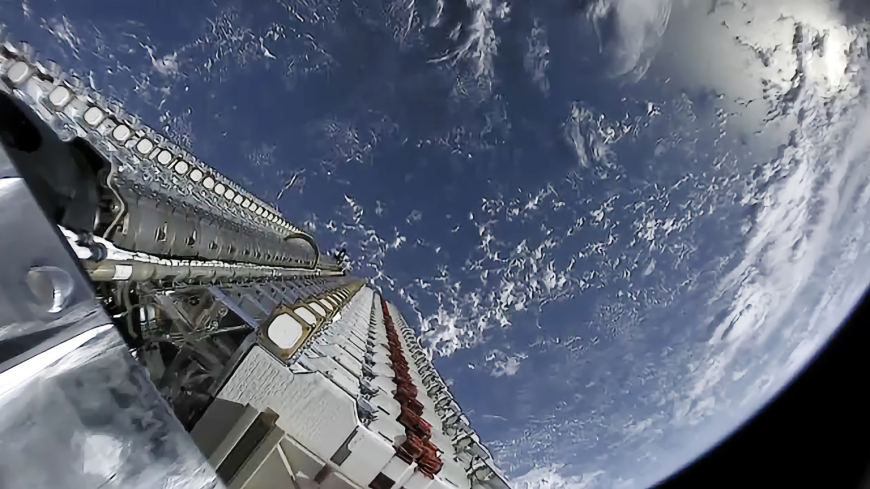

Now that idea is edging closer to reality. SpaceX has formally sought regulatory approval to deploy solar-powered orbital data centres distributed across as many as one million satellites. The proposal envisions shifting up to 100 gigawatts of computing capacity off Earth. Reports suggest that some of these AI satellites could even be assembled on the moon.

"By far the cheapest place to put AI will be space in 36 months or less," Musk recently said during a podcast hosted by John Collison, co-founder of Stripe.

Others share similar ambitions. Leaders within xAI have reportedly wagered that 1% of global compute will be operating in orbit by 2028. Google, which holds a substantial stake in SpaceX, has unveiled a space-focused AI initiative called Project Suncatcher, with prototype missions slated for 2027. Meanwhile, startup Starcloud, backed by Google and Andreessen Horowitz, has filed plans for an 80,000-satellite constellation. Even Jeff Bezos has publicly suggested that orbital computing represents a significant part of the future.

Yet beyond the excitement, the financial and technical realities are daunting.

The cost gap between orbit and Earth

For now, terrestrial data centres maintain a clear economic advantage. Space engineer Andrew McCalip has developed a model comparing the two. His estimates indicate that a 1-gigawatt orbital data centre could cost roughly $42.4 billion—nearly three times the cost of a comparable facility on Earth. The steep premium stems primarily from manufacturing satellites and launching them into orbit.

Closing that gap will require advances across multiple technologies, substantial capital investments, and a far more mature supply chain for space-grade hardware. It also assumes that land-based infrastructure costs rise over time due to growing demand for energy and materials.

Launch economics and the Starship factor

Launch costs remain the single biggest variable in any space-based business case. SpaceX has reduced orbital launch prices significantly, yet even lower costs are required to make orbital datacentres financially viable. The plan's feasibility is closely tied to SpaceX's completion of its long-running Starship program, which remains not fully operational and has yet to achieve sustained orbital flights. A third-generation Starship vehicle is expected to launch in the coming months.

Currently, the reusable Falcon 9 rocket delivers payloads to orbit at about $3,600 per kilogram. According to Project Suncatcher's white paper, costs closer to $200 per kilogram—an 18-fold reduction—would be necessary. Those levels are projected for the 2030s. At such prices, energy from orbiting solar-powered satellites could rival the cost of terrestrial electricity.

However, analysts question whether SpaceX would immediately pass on dramatic savings to customers. Economists at the consultancy Rational Futures argue that, as with Falcon 9, SpaceX is unlikely to price launches dramatically below competitors such as Blue Origin, whose New Glenn rocket is expected to cost approximately $70 million per mission. Charging far less could mean forfeiting potential revenue.

"There are not enough rockets to launch a million satellites yet," Matt Gorman of Amazon Web Services said at a recent event. "If you think about the cost of getting a payload in space today, it's massive. It is just not economical."

Satellite production hurdles

Beyond launch, satellite manufacturing is a major cost centre. While many projections assume Starship will reduce costs per kilogram to the hundreds of dollars, current satellites cost $1,000 per kilogram.

SpaceX has driven down costs while building Starlink, its global communications network, and hopes similar scale efficiencies will apply to AI satellites. A constellation numbering in the hundreds of thousands or even a million units would lower per-unit costs through mass production.

Still, these satellites must support powerful GPUs. That requires expansive solar arrays, advanced thermal management systems, and laser-based communication links—each adding weight and complexity.

A 2025 Project Suncatcher white paper compared power costs. On Earth, data centres typically spend between $570 and $3,000 annually per kilowatt. In orbit, however, accounting for satellite construction, launch, and maintenance, power could cost roughly $14,700 per kilowatt per year. Until hardware costs decline substantially, orbital energy remains expensive.

The unforgiving space environment

Managing heat in orbit is more challenging than commonly assumed. Without an atmosphere, heat cannot dissipate through convection; instead, it must radiate away. Large radiators are required, increasing surface area and mass.

"You're relying on very large radiators to dissipate heat into the blackness of space," said Mike Safyan of Planet Labs, which is collaborating on prototype satellites for Project Suncatcher slated for 2027.

Radiation presents another obstacle. Cosmic rays degrade semiconductor performance and can cause bit-flip errors that corrupt data. Shielding, rad-hardened components, or redundancy measures add mass and cost. Google has reportedly tested tensor processing units with particle beams to simulate radiation exposure, while SpaceX has acquired equipment for similar experimentation.

Solar panels add further complexity. Orbital panels can generate five to eight times more power than terrestrial ones and remain sunlit for up to 90% of the day in certain orbits. However, radiation accelerates degradation, particularly for silicon panels used in systems such as Starlink and Amazon Kuiper. That may limit AI satellites to roughly five years of service life, compressing return-on-investment timelines.

Some observers argue that rapid AI chip advancement reduces the concern over shorter lifespans. Hardware often becomes outdated within a similar time frame.

Training versus inference in orbit

A critical question remains: what tasks should orbital data centres handle? Large-scale model training typically requires thousands of GPUs operating in close coordination. Today's terrestrial data centres connect TPU clusters at hundreds of gigabits per second. Current inter-satellite laser links peak at around 100 Gbps, creating a bottleneck.

Project Suncatcher proposes forming 81 satellites close enough to use high-bandwidth transceivers similar to those used on Earth. Maintaining such formations requires precise autonomy and debris-avoidance capabilities.

Inference workloads, by contrast, require fewer GPUs and may be well suited to single-satellite deployments. Many believe inference—serving queries, powering voice agents, or responding to chatbot prompts could represent the first viable orbital AI business model.

"Training is not the ideal thing to do in space," said Starcloud CEO Philip Johnston, who suggests inference will dominate early use cases. His company claims to be already generating revenue from in-orbit inference.

SpaceX's regulatory filings indicate satellites delivering approximately 100 kilowatts of compute per ton, roughly double the capacity of existing Starlink units. These satellites would interconnect via Starlink's laser network, which is described as capable of petabit-level throughput.

Following SpaceX's acquisition of xAI, the company now operates across both terrestrial and orbital AI infrastructure. This dual approach allows it to scale where economics make the most sense, whether constrained by permitting or capital expenditure on the ground.

Ultimately, as Andrew McCalip put it, compute is fungible. "A FLOP is a FLOP; it doesn't matter where it lives. [SpaceX] can scale until it hits bottlenecks on the ground, and then fall back to space deployments." The promise of orbital AI is ambitious. The economics, at least for now, remain unforgiving.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0