Okay, I’m slightly less mad about that ‘Magnificent Ambersons’ AI project

A closer look at the AI project tied to The Magnificent Ambersons shows why some critics are warming to it, despite ongoing concerns about technology and film heritage.

When a startup revealed plans last fall to reconstruct lost scenes from Orson Welles’ classic film The Magnificent Ambersons using generative AI, my reaction was sceptical. More than that, I couldn’t understand why anyone would invest time and resources into a project that seemed destined to anger film purists while offering little obvious commercial upside.

This week, a detailed profile by The New Yorker’s Michael Schulman sheds new light on the effort. At the very least, it clarifies why the startup Fable and its founder, Edward Saatchi, are pursuing the idea: the project appears to be rooted in a sincere admiration for Welles and his body of work.

Saatchi, whose father co-founded the advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi, described growing up watching films in a private screening room with parents he called “movie mad.” He said he first encountered Ambersons at the age of twelve.

The profile also explores why The Magnificent Ambersons, though far less famous than Welles’ debut Citizen Kane, continues to exert such fascination. Welles himself once said it was a “much better picture” than Kane. But after a disastrous preview screening, the studio removed 43 minutes of footage, imposed a rushed, unconvincing happy ending, and eventually destroyed the deleted scenes to free up space in its vaults.

“To me, this is the holy grail of lost cinema,” Saatchi said. “It just seemed intuitively that there would be some way to undo what had happened.”

Saatchi is hardly the first admirer of Welles to imagine reconstructing the missing material. Fable is collaborating with filmmaker Brian Rose, who previously spent years attempting something similar through animated sequences based on the script, archival photographs, and Welles’ own notes. Rose said that after screening his work for friends and family, “a lot of them were scratching their heads.”

As a result, although Fable is relying on more advanced tools — shooting scenes in live action and later layering them with digital recreations of the original actors and their voices — the project can be seen as a more polished, better-funded extension of Rose’s earlier effort. At its core, it remains a fan-driven attempt to glimpse what Welles may have intended.

Notably, while The New Yorker article includes clips from Rose’s animations and still images of Fable’s AI-generated performers, it does not show any footage from Fable’s live-action AI hybrid sequences.

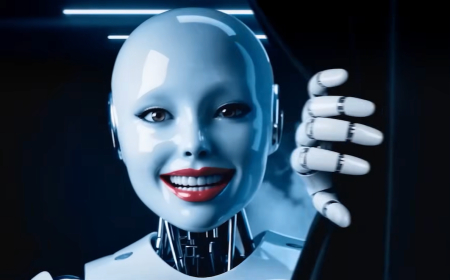

By Fable’s own account, the undertaking faces serious obstacles. These range from technical mistakes, such as accidentally generating a two-headed version of actor Joseph Cotten, to more subjective challenges, such as recreating the film’s intricate visual style. Saatchi even noted a “happiness” issue, with the AI tending to make the female characters appear oddly cheerful in moments that should not convey that emotion.

As for whether the reconstructed footage will ever be publicly released, Saatchi acknowledged that failing to consult Welles’ estate before announcing the project was “a total mistake.” Since then, he has reportedly been working to gain approval from both the estate and Warner Bros., which holds the film’s rights. Welles’ daughter, Beatrice, told Schulman that while she remains sceptical,” she now believes “they are going into this project with enormous respect toward my father and this beautiful movie.”

Actor and biographer Simon Callow, who is currently writing the fourth volume of his multi-book Welles biography, has also agreed to advise the project. He described the effort as a “great idea.” Callow is a longtime family friend of the Saatchis.

Still, not everyone is persuaded. Melissa Galt said her mother, actress Anne Baxter, would “not have agreed with that at all.”

“It’s not the truth,” Galt said. “It’s a creation of someone else’s truth. But it’s not the original, and she was a purist.”

Although I’ve grown more sympathetic to Saatchi’s intentions, I ultimately find myself agreeing with Galt. At best, the project will produce curiosity—a speculative vision of what the film might have been.

Galt’s recollection of her mother’s belief that “once the movie was done, it was done” brought to mind a recent essay by writer Aaron Bady, who compared AI to the vampires in Sinners. Bady argued that both vampires and AI fall short artistically because “what makes art possible” is an awareness of mortality and limits.

“There is no work of art without an ending, without the point at which the work ends (even if the world continues),” he wrote. “Without death, without loss, and without the space between my body and yours, separating my memories from yours, we cannot make art or desire or feeling.”

Viewed through that lens, Saatchi’s conviction that there must be “some way to undo what had happened” feels less visionary and more like an unwillingness to accept that some losses are final. It may not be entirely different from a startup founder claiming they can eliminate grief — or from a studio executive insisting that The Magnificent Ambersons required a happy ending.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0